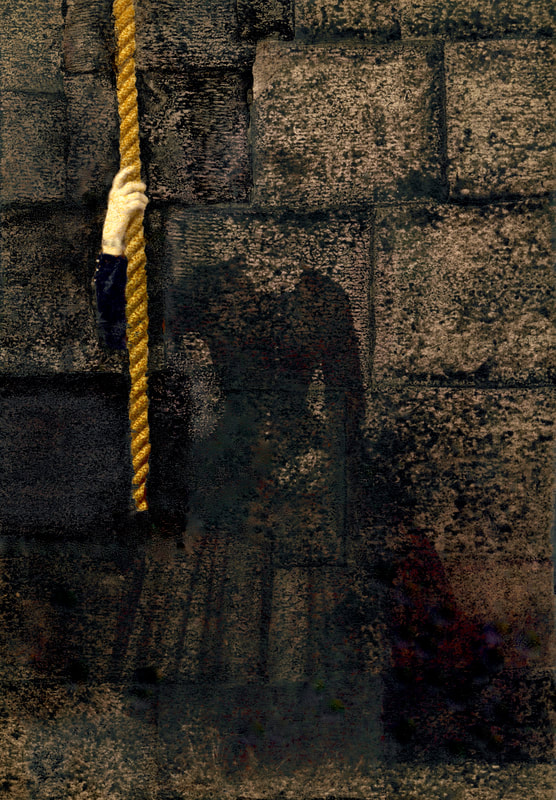

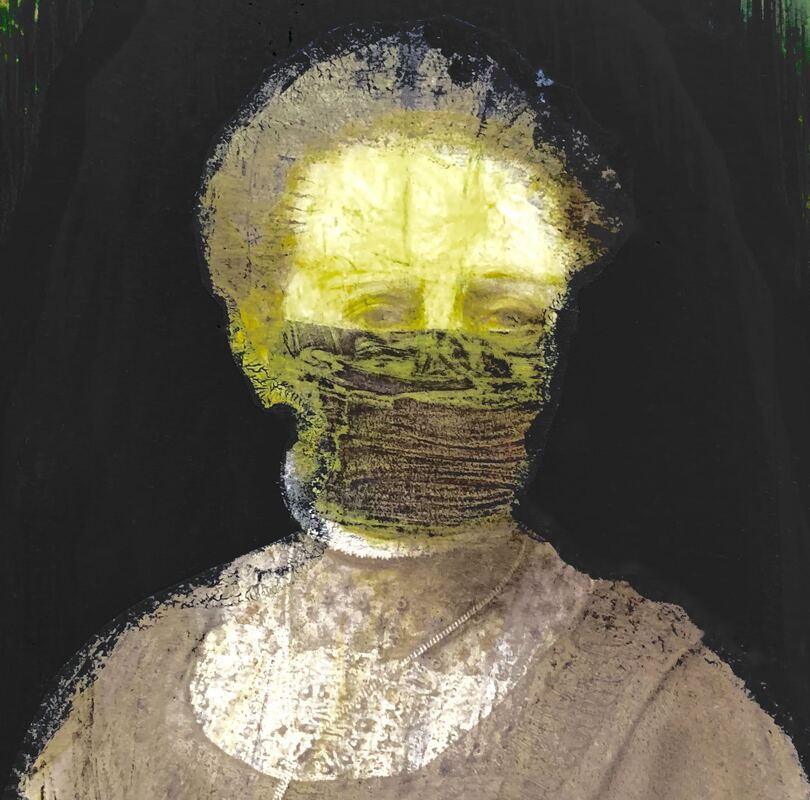

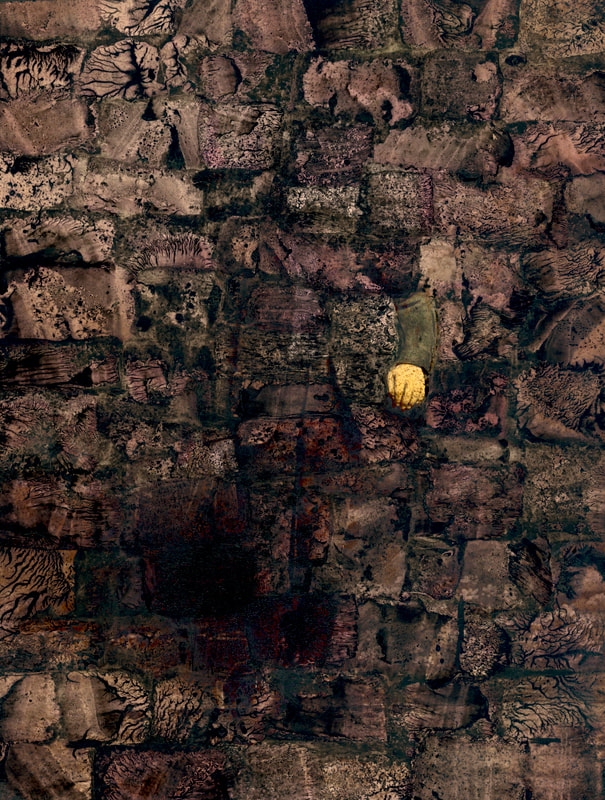

Julie Blankenship is an artist and curator, based in San Francisco. As the AIDS pandemic swept the country in the ‘90’s and many friends died, the emotional weight of those losses seeped into her work and materials. She’s known for using found portraits, often damaged, identities lost. Working directly on small, black and white, nineteenth century photographs, she hand-alters them by painting, collaging and layering the images with ink, dust and glue; then makes large, archival digital prints based on these works. Inspired by archives, the work explores beauty, history and the changeable nature of identity. Originally, the photos encouraged a feeling of connection, but she interrupts these (now unknown) narratives—deconstructing, reassembling and recycling them into works whose beauty arises out of processes that nearly destroy the materials. They allude to metamorphoses, dark histories and gothic struggles, in the context of today’s political and ecological upheaval.

Her work has been exhibited widely, including American Institute of Architects Architecture+Design Gallery, Camerawork, Amsterdams Centrum voor Fotografie and most recently at CICA Museum in Seoul. As visiting professor, she taught photography and interdisciplinary art at the San Francisco Art Institute and San Francisco State University’s renowned Inter-Arts Center. She opened Visual Aid Gallery while Executive Director of Visual Aid, an arts/social justice organization serving artists with AIDS. Recently, her work was featured on the cover of Egaeus Press’ Of One Free Will, a book of speculative fiction by Farah Rose Smith; and published in international literary magazines including Blood Bath, London Reader, Sein und Werden, Foxhole, High Shelf Press, and Punt Volat. This summer, she appeared in the KQED documentary feature film Mrs. Vera's Daybook.

Her work has been exhibited widely, including American Institute of Architects Architecture+Design Gallery, Camerawork, Amsterdams Centrum voor Fotografie and most recently at CICA Museum in Seoul. As visiting professor, she taught photography and interdisciplinary art at the San Francisco Art Institute and San Francisco State University’s renowned Inter-Arts Center. She opened Visual Aid Gallery while Executive Director of Visual Aid, an arts/social justice organization serving artists with AIDS. Recently, her work was featured on the cover of Egaeus Press’ Of One Free Will, a book of speculative fiction by Farah Rose Smith; and published in international literary magazines including Blood Bath, London Reader, Sein und Werden, Foxhole, High Shelf Press, and Punt Volat. This summer, she appeared in the KQED documentary feature film Mrs. Vera's Daybook.

Published on March 8th 2021. Artist responses collected in months previous.

What hurdles have you overcome this year and how have they affected your art practice?

I’ve plagued by minor physical issues, and spent several months on crutches. Getting to my studio meant navigating five steep flights of stairs, or using an ancient, unreliable freight elevator. I’m usually very self-sufficient, so asking for help was agony. Once in my studio, I was fine--my art practice was my saving grace. Last spring, news that the San Francisco Art Institute was facing closure hit me hard. Financial issues, exacerbated by circumstances brought about by covid, were existential threats to the school. It’s been a painful time, and hugely stressful for everyone in the SFAI community. Having studied and taught at SFAI, it’s in my DNA. As a center of innovation and incubator for creativity, closing would be a tragic loss for the art world. Along with many alumni, artists and core supporters, I’m volunteering to support efforts to save the school. The school was able to open for classes this semester and will persevere. SFAI is being revitalized, and going through a revision process, with the goal of coming back well-positioned with the openness, creativity, resilience and strength to face the challenges of the changing world.

How has your art practice been affected by the pandemic?

I run a small, group studio space in a large, industrial building. Since the pandemic began, I rarely see a soul in the building, much less my studio mates. Although I enjoy working alone, I’ve found their absence oppressive. I was down in the dumps without seeing them every day and the studio, usually filled with the companionable background sounds of artists at work, was silent. In recent weeks, my studio mates have begun to return. I’ve seen them more often and am very glad of their company (socially distanced, of course). I’ve been worried that our band of artists might be broken up or that we’ll lose our studios, but so far none of that has happened. I hope we’ll make it through the winter intact.

What support systems have you put in place to help keep your practice thriving amidst these unforeseeable circumstances?

Friends are always good for putting things into perspective, and doling out doses of black humor. I phone friends often, especially on days when the world presses in. This is a challenging and scary time for many of my friends, who are living with AIDS or otherwise compromised health. I’m inspired by their disciplined self-care and how they’re able to draw on years of experience in facing their own fears. They are my models of equanimity and self-sufficiency, reminding me that we’ve been through hard times before and we’ll most likely survive this terrible era. If it doesn’t kill you, it makes you stronger. Recently, a relationship with an artist friend, who I met back in art school, has gained new energy. We’ve begun to meet online regularly to discuss art and ideas, problem solve around obstacles, and encourage each other to continue to take risks. We’re working towards an exhibition together. Although our work is very different, we’ve discovered that we’re working on similar themes--exploring obsession, residue, evidence, death, presence/absence, time, identity, and archives.

What methods do you employ to stay resilient in your art practice? What tips would you recommend to other artists who find staying resilient difficult?

Outside perspectives are essential, especially for creative work. Never ask for feedback, unless you want to hear it. If you choose your sources with care, their musings, ideas, resources and support can be enlivening and enriching. Portfolio reviews, offered online by a NYC gallerist, have been an opportunity for me to focus on new ways of editing, presenting and talking about my work. Attending lectures and taking online classes at NY Center for the Book has been inspiring and a wonderful distraction. I’ve experimented with printmaking techniques, book cover design and constructing portfolio boxes. Volunteer work is fulfilling and a great way to connect with other people who have passions and beliefs in common. It’s empowering to work towards something positive during this dark time.

What have you learned about yourself as an artist this year?

I’ve always been obsessed with books. Growing up in a military family that moved frequently gave me a sense of disequilibrium and dislocation. As a child, reading was my salvation. It was very grounding. Recently, I’ve been thrilled to have my work on the cover of a book and in international magazines. Having my work in print and out in the world gives me an inordinate amount of pleasure. I’ve been fighting the urge to return to the darky, murky spectrum I used years ago—muddy browns, prussian blue, blacks and greys. In recent years, I developed a love for color. I’m known for my use of mercurochrome pinks and reds, vibrant yellow orange, chartreuse and electric blues in my work. Lately, I’ve been experimenting with pairing colors from the two palettes. Obsessing and avoiding thinking about the pandemic and politics uses so much of my brain power and energy that at times it’s been difficult to focus on my work. I need to have a stillness and calm within, in order to create. If that’s not possible, then I continue to make work. If in doubt, chop wood and carry water.

What hurdles have you overcome this year and how have they affected your art practice?

I’ve plagued by minor physical issues, and spent several months on crutches. Getting to my studio meant navigating five steep flights of stairs, or using an ancient, unreliable freight elevator. I’m usually very self-sufficient, so asking for help was agony. Once in my studio, I was fine--my art practice was my saving grace. Last spring, news that the San Francisco Art Institute was facing closure hit me hard. Financial issues, exacerbated by circumstances brought about by covid, were existential threats to the school. It’s been a painful time, and hugely stressful for everyone in the SFAI community. Having studied and taught at SFAI, it’s in my DNA. As a center of innovation and incubator for creativity, closing would be a tragic loss for the art world. Along with many alumni, artists and core supporters, I’m volunteering to support efforts to save the school. The school was able to open for classes this semester and will persevere. SFAI is being revitalized, and going through a revision process, with the goal of coming back well-positioned with the openness, creativity, resilience and strength to face the challenges of the changing world.

How has your art practice been affected by the pandemic?

I run a small, group studio space in a large, industrial building. Since the pandemic began, I rarely see a soul in the building, much less my studio mates. Although I enjoy working alone, I’ve found their absence oppressive. I was down in the dumps without seeing them every day and the studio, usually filled with the companionable background sounds of artists at work, was silent. In recent weeks, my studio mates have begun to return. I’ve seen them more often and am very glad of their company (socially distanced, of course). I’ve been worried that our band of artists might be broken up or that we’ll lose our studios, but so far none of that has happened. I hope we’ll make it through the winter intact.

What support systems have you put in place to help keep your practice thriving amidst these unforeseeable circumstances?

Friends are always good for putting things into perspective, and doling out doses of black humor. I phone friends often, especially on days when the world presses in. This is a challenging and scary time for many of my friends, who are living with AIDS or otherwise compromised health. I’m inspired by their disciplined self-care and how they’re able to draw on years of experience in facing their own fears. They are my models of equanimity and self-sufficiency, reminding me that we’ve been through hard times before and we’ll most likely survive this terrible era. If it doesn’t kill you, it makes you stronger. Recently, a relationship with an artist friend, who I met back in art school, has gained new energy. We’ve begun to meet online regularly to discuss art and ideas, problem solve around obstacles, and encourage each other to continue to take risks. We’re working towards an exhibition together. Although our work is very different, we’ve discovered that we’re working on similar themes--exploring obsession, residue, evidence, death, presence/absence, time, identity, and archives.

What methods do you employ to stay resilient in your art practice? What tips would you recommend to other artists who find staying resilient difficult?

Outside perspectives are essential, especially for creative work. Never ask for feedback, unless you want to hear it. If you choose your sources with care, their musings, ideas, resources and support can be enlivening and enriching. Portfolio reviews, offered online by a NYC gallerist, have been an opportunity for me to focus on new ways of editing, presenting and talking about my work. Attending lectures and taking online classes at NY Center for the Book has been inspiring and a wonderful distraction. I’ve experimented with printmaking techniques, book cover design and constructing portfolio boxes. Volunteer work is fulfilling and a great way to connect with other people who have passions and beliefs in common. It’s empowering to work towards something positive during this dark time.

What have you learned about yourself as an artist this year?

I’ve always been obsessed with books. Growing up in a military family that moved frequently gave me a sense of disequilibrium and dislocation. As a child, reading was my salvation. It was very grounding. Recently, I’ve been thrilled to have my work on the cover of a book and in international magazines. Having my work in print and out in the world gives me an inordinate amount of pleasure. I’ve been fighting the urge to return to the darky, murky spectrum I used years ago—muddy browns, prussian blue, blacks and greys. In recent years, I developed a love for color. I’m known for my use of mercurochrome pinks and reds, vibrant yellow orange, chartreuse and electric blues in my work. Lately, I’ve been experimenting with pairing colors from the two palettes. Obsessing and avoiding thinking about the pandemic and politics uses so much of my brain power and energy that at times it’s been difficult to focus on my work. I need to have a stillness and calm within, in order to create. If that’s not possible, then I continue to make work. If in doubt, chop wood and carry water.

Julie Blankenship