In recent months, Julie Blankenship’s photo-based, mixed media work was included in the exhibitions Time Space Existence, at the European Cultural Center (Venice, Italy); and Photo Trouvee’s Monochromatic show. It was recently published in Photo Trouvee photography magazine; and literary journals Midnight Chem, and Brazenhead Review (USA), and Beyond Words (Berlin); and on the cover of the book Hard to Find: An Anthology of New Southern Gothic. Her work has been exhibited widely, including shows at Amsterdam Center for Photography (Amsterdam); Korean Culture and Arts Foundation (Seoul); Walter/McBean, and Joseph Chowning Gallery (San Francisco); and appeared in publications including Blood Bath (Edinburgh), Sein Und Werden (Manchester) and Poets & Writers Magazine (USA). Today, she is Director of Visual Aid Projects+Archives. As head of Visual Aid, an arts/social justice nonprofit organization, she founded Visual Aid Gallery, and curated exhibitions focusing on the work of artists with AIDS and other life-threatening illnesses. She taught at the Interdisciplinary Art Center at San Francisco State University; and the San Francisco Art Institute, where she had previously studied photography and painting.

Published on March 3rd, 2024. Artist responses collected in months previous.

What are you working on these days?

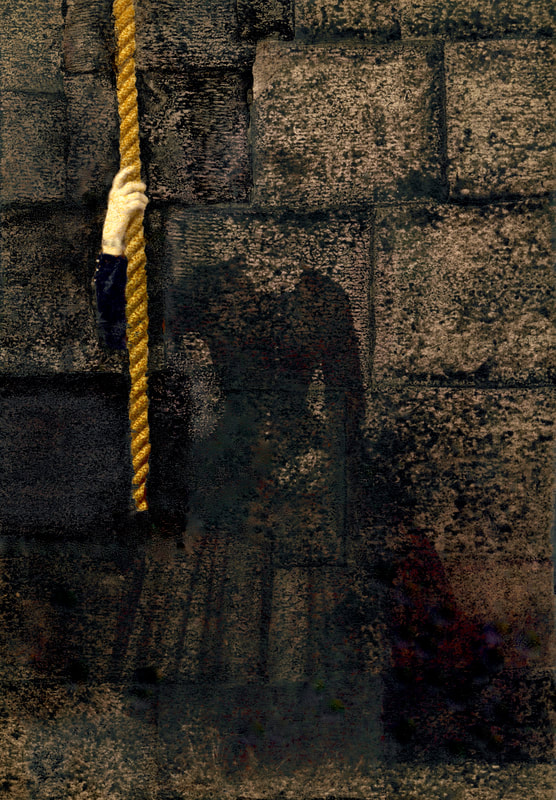

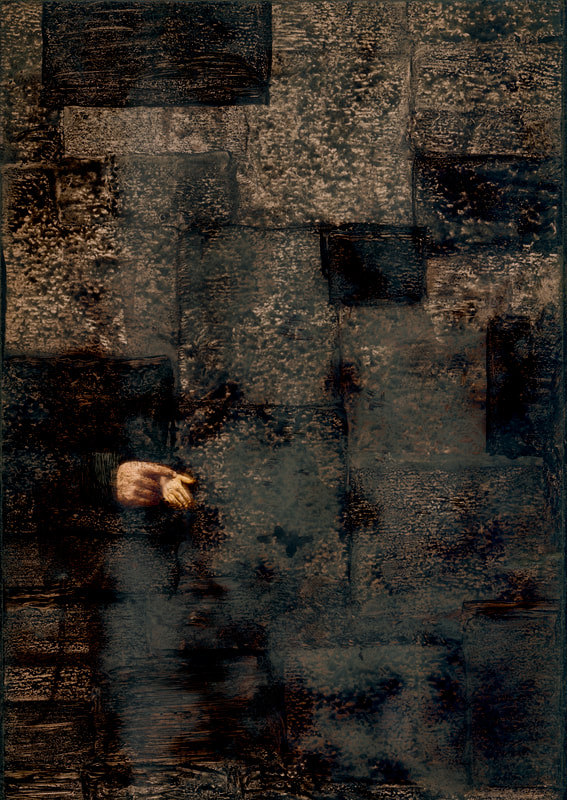

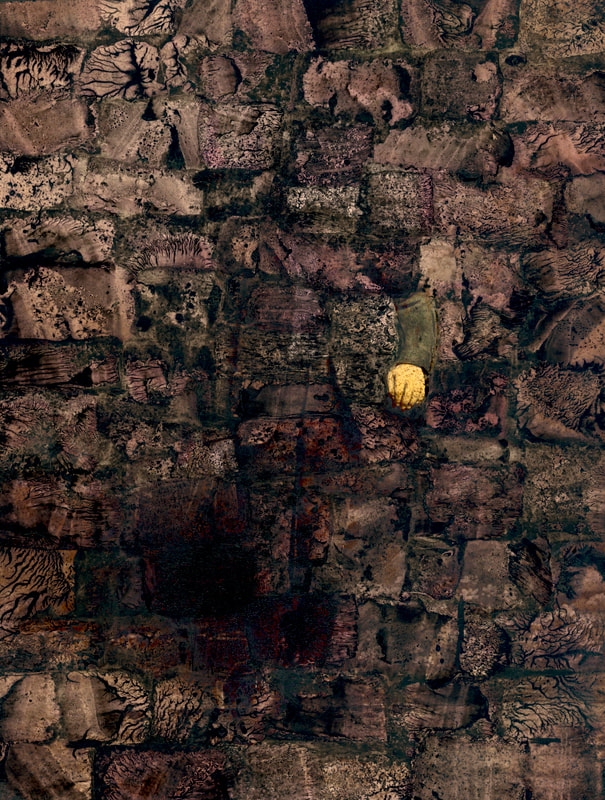

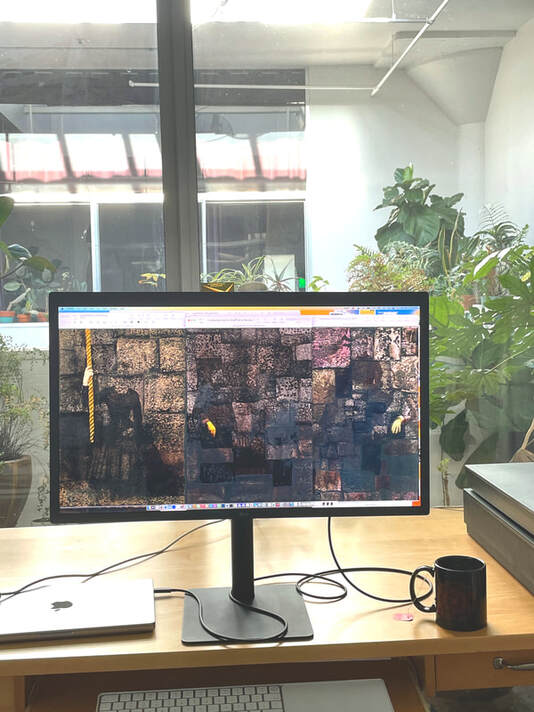

I’m in the midst of several series of altered, found photographs, including the works shown here, from the series Brickworks. Recycling black and white, studio portraits that are over 150 years old and discarded by their owners, I paint directly on their worn surfaces. I love working with a limited palette of materials, especially with ink, which can act in unpredictable ways. As a piece progresses, ink soaks through the scarred, skin-like emulsion of the photograph; and seeps into its cardboard substrate, swelling ancient cotton fibers. Filaments often rise up, looking like unruly hairs, and dust particles on the surface grab ahold of pigment, creating a mottled or stippled appearance, and enhancing marks and scratches that reveal the lifespan of the photograph as an object.

What has been going well for you in your art career and life recently?

Travel has been a revelation. During a long-awaited visit to Berlin, the range and diversity of art and artists represented in exhibitions at alternative institutions, supported by the state, were a joy to experience. The Movement of People Working, 24-hour installation for Phill Niblock’s 90th birthday, with projections of his films of people doing manual labor, and his compositions performed live by young musicians at an alternative concert hall, was emotional and mesmerizing. KW, a nonprofit gallery in a former industrial dairy, presented a compelling Coco Fusco retrospective. Luise. Archaeology of an injustice, a photo-based installation by Stefan Weger, was extremely powerful. His photographs confronted the forgotten story of how actions by his family led to the Gestapo’s execution of a 15-year-old Polish boy, Walerian Wróbel, who was a forced laborer on the family farm. The exhibition was staged at the only preserved forced-labor camp (one of 1,500+ camps formerly in Berlin). After a wide-ranging discussion with the artist, I was given a haunting, personal tour of the camp. I came away more aware than ever of how in the US, we’re barely at the very beginning of remembering, and confronting difficult truths of our past as a nation.

What is something new that you have discovered this past year that is meaningful or helpful for you?

This year, I took classes on constructing artists books, researched wildly varying formats, and made experimental dummies for several accordion books, using printed reproductions of my work. I was also part of an excellent artists residency sponsored by Photo Trouvee. I bonded with two women artists, and the three of us have been meeting weekly, ever since. Their courage and tenacity in engaging with their own work, depth of knowledge of materials and techniques, and personal and artistic support has been extremely helpful.

Briefly walk us through your process of making art or thinking through a new project, focusing on what's most important to you as you create.

Often working with found objects that appear to have straight-forward story lines, such as photographic portraits, I spend a lot of time looking, thinking, and meditating. I do research, experiment, and test materials. As I begin to tease out underlying themes, tangential threads of ideas and emotions that come up are valued and often followed, though they may lead away from initial concepts. It’s important to accept that, in the end, not all threads will be tied together into a neat package. Discerning which threads to leave dangling, and which to weave back in, is an important part of the process. I’ve recently begun working on an installation about my family and growing up in a stressful home environment, with a lack of stability due to frequent moves, alcoholism and political activities of my parents. Not aiming to tell a straightforward story (which would be impossible anyhow), I’m instead developing a non-linear narrative, based on the way I perceived my environment--confusing, filled with seemingly-disjointed details, and ungrounded. The focus will be on found objects, books and photographs, all organized by time and geography. Which all sounds very much more orderly than it will actually be.

Is there anything else that you would like to share with our readers?

Traditional studio portraits are often stilted and generic, codifying the striving of those pictured. By responding to ways in which the portraits embodied aspirations and fantasy, the moment a photograph was made, and the poignance and solemnity of the occasion, come into focus. Through the process of altering these photographs, the images become something else altogether, evoking sparks of humanity. Ghostly fragments of invented stories, and glimmers of spirit images appear through decaying walls, or membranes of time and space. Inspired by details of forgotten lives and archives, these works allude to metamorphoses, dark histories and gothic struggles, in the context of today’s upheavals.

What are you working on these days?

I’m in the midst of several series of altered, found photographs, including the works shown here, from the series Brickworks. Recycling black and white, studio portraits that are over 150 years old and discarded by their owners, I paint directly on their worn surfaces. I love working with a limited palette of materials, especially with ink, which can act in unpredictable ways. As a piece progresses, ink soaks through the scarred, skin-like emulsion of the photograph; and seeps into its cardboard substrate, swelling ancient cotton fibers. Filaments often rise up, looking like unruly hairs, and dust particles on the surface grab ahold of pigment, creating a mottled or stippled appearance, and enhancing marks and scratches that reveal the lifespan of the photograph as an object.

What has been going well for you in your art career and life recently?

Travel has been a revelation. During a long-awaited visit to Berlin, the range and diversity of art and artists represented in exhibitions at alternative institutions, supported by the state, were a joy to experience. The Movement of People Working, 24-hour installation for Phill Niblock’s 90th birthday, with projections of his films of people doing manual labor, and his compositions performed live by young musicians at an alternative concert hall, was emotional and mesmerizing. KW, a nonprofit gallery in a former industrial dairy, presented a compelling Coco Fusco retrospective. Luise. Archaeology of an injustice, a photo-based installation by Stefan Weger, was extremely powerful. His photographs confronted the forgotten story of how actions by his family led to the Gestapo’s execution of a 15-year-old Polish boy, Walerian Wróbel, who was a forced laborer on the family farm. The exhibition was staged at the only preserved forced-labor camp (one of 1,500+ camps formerly in Berlin). After a wide-ranging discussion with the artist, I was given a haunting, personal tour of the camp. I came away more aware than ever of how in the US, we’re barely at the very beginning of remembering, and confronting difficult truths of our past as a nation.

What is something new that you have discovered this past year that is meaningful or helpful for you?

This year, I took classes on constructing artists books, researched wildly varying formats, and made experimental dummies for several accordion books, using printed reproductions of my work. I was also part of an excellent artists residency sponsored by Photo Trouvee. I bonded with two women artists, and the three of us have been meeting weekly, ever since. Their courage and tenacity in engaging with their own work, depth of knowledge of materials and techniques, and personal and artistic support has been extremely helpful.

Briefly walk us through your process of making art or thinking through a new project, focusing on what's most important to you as you create.

Often working with found objects that appear to have straight-forward story lines, such as photographic portraits, I spend a lot of time looking, thinking, and meditating. I do research, experiment, and test materials. As I begin to tease out underlying themes, tangential threads of ideas and emotions that come up are valued and often followed, though they may lead away from initial concepts. It’s important to accept that, in the end, not all threads will be tied together into a neat package. Discerning which threads to leave dangling, and which to weave back in, is an important part of the process. I’ve recently begun working on an installation about my family and growing up in a stressful home environment, with a lack of stability due to frequent moves, alcoholism and political activities of my parents. Not aiming to tell a straightforward story (which would be impossible anyhow), I’m instead developing a non-linear narrative, based on the way I perceived my environment--confusing, filled with seemingly-disjointed details, and ungrounded. The focus will be on found objects, books and photographs, all organized by time and geography. Which all sounds very much more orderly than it will actually be.

Is there anything else that you would like to share with our readers?

Traditional studio portraits are often stilted and generic, codifying the striving of those pictured. By responding to ways in which the portraits embodied aspirations and fantasy, the moment a photograph was made, and the poignance and solemnity of the occasion, come into focus. Through the process of altering these photographs, the images become something else altogether, evoking sparks of humanity. Ghostly fragments of invented stories, and glimmers of spirit images appear through decaying walls, or membranes of time and space. Inspired by details of forgotten lives and archives, these works allude to metamorphoses, dark histories and gothic struggles, in the context of today’s upheavals.

Find Julie Blankenship on Instagram