Julie Blankenship lives and works in San Francisco, California. She is an artist, curator and dreamer. She grew up in a navy family, and moved constantly. Living with a feeling of unease and not belonging—she developed a rich inner life, nourished by reading and climbing trees. She has an MFA in painting and photography from San Francisco Art Institute and later taught interdisciplinary art and photography at SFAI and SF State University. For thirteen years, she served as Executive Director of Visual Aid, an organization that encouraged the creative work of artists with AIDS. She founded Visual Aid Gallery, and curated numerous exhibitions. Focusing on service and bringing home the bacon, her art career took a back seat for a while. In recent years, she has a full time studio practice and a new/innovative body of work that builds on her long time commitment to working with found photographs.

Published on May 7th 2020. Artist responses collected in months previous.

What projects are you working on right now?

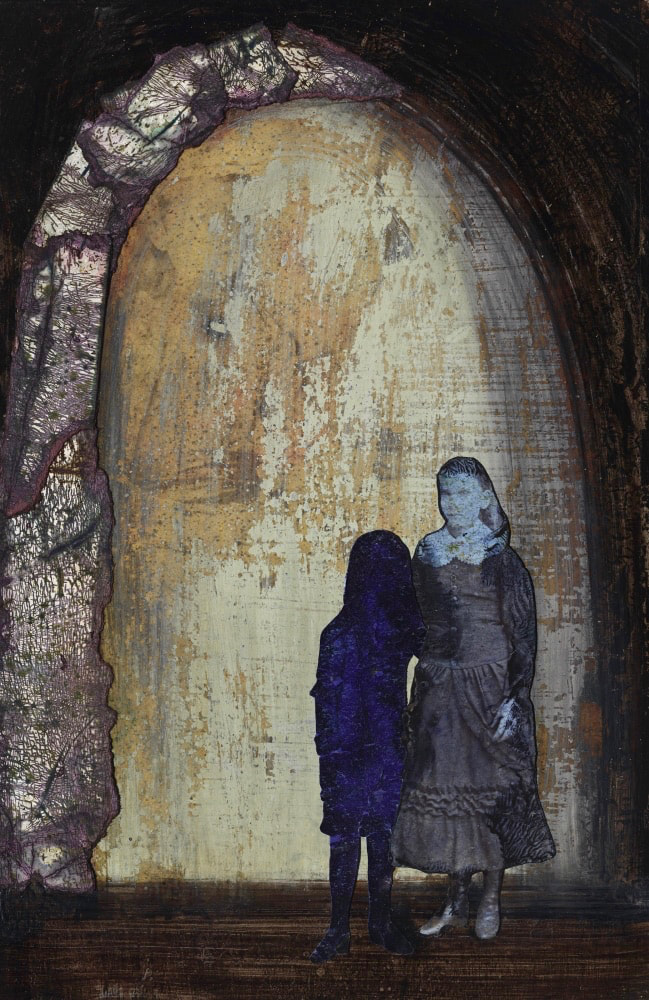

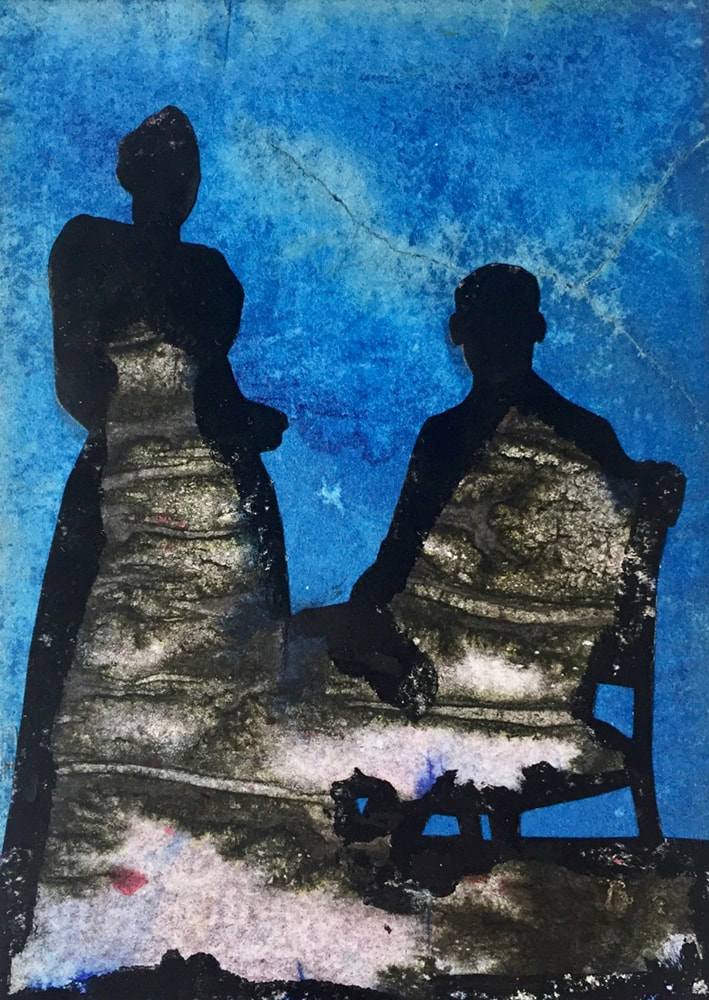

I'm currently working on submitting my work for publication in literary magazines and applying with a friend for an exhibition at a gallery in New Orleans. I use found, black and white photographs from the nineteenth century, called cartes de visite and cabinet cards, to make 4x6" collages. Alterations are done by hand on a small scale, using ink, dust, and glue, then reproduced digitally to create 8x10” portfolio prints and l30x40" archival photographic prints. My works respond to ways in which, throughout the industrial revolution, photography and advertising were employed in the construction of identity. Standards of living improved for some, but income disparity increased. The U.S., an agricultural economy fueled by slave labor, underwent a painful transformation, reinventing itself as a consumer culture in an increasingly industrialized environment. Originally, these photographs encouraged feelings of connection to distant people, places and times. I interrupt these (now unknown) narratives—recycling and creating new meanings, responding to the content, and the physical objects themselves by working the surfaces. I deconstruct and reassemble flotsam and jetsam from the industrial revolution into works whose beauty arises out of a process that nearly destroys the materials, alluding to metamorphoses, dark histories and gothic struggles.

How do you keep yourself accountable in your practice?

I’ve become more focused—taking pleasure in working in my studio most days, and staying true to my passion—making art that reveals the transfixing beauty, ugliness and horror of the world and what it means to be human. I take my own measures of success very seriously and am usually less concerned about others’ ideas of what I’m supposed to be doing. Applying for publication and exhibition opportunities motivates me to keep my business papers in order. I research artists calls to identify galleries and publications that are a good match for my work. I focus on details of what matters, but I do things I don’t enjoy—such as framing—in the simplest manner possible. I’m usually able to give myself credit for successes, take responsibility for mistakes and let go of disappointments. I have coffee with friends and mentors to discuss progress on our work, and schedule studio visits. These meetings cheer and strengthen me, revealing new ways of seeing my work, and help overcome obstacles. I treasure my studio time and make time to give others a hand when I can.

How do you stay motivated to pursue your creative work?

I get so much joy from the process of making art. I love my materials—the beauty of ink, the images and textures of nineteenth century photographs. I try to get in the right mindset to work. On days I don’t feel motivated, I alternate between doing easy things and hard things. I like trying new things, inventing new ways of working surfaces, inventing beautiful/hideous color combinations. I avoid people who aren't supportive of my work. I read, dream, visit archives, do research and look at others' work. I try to eliminate mundane problems in my work so I can focus on the important stuff. That means I make work that’s light enough for me to carry, small enough to store, using materials I can afford. Focusing on my strengths is helpful. Taking on new, possibly scary, challenges excites me. I try to leave jealousy behind. As a kid, although I visited art museums and read about art, I never knew women artists existed. That absence lights a fire in me to claim my voice and communicate my own inner world. I’m tenacious. I’m comforted knowing I’ll never, ever quit, no matter what.

Where do you hope to be 10 years from now and what would you like to say to yourself?

In ten years, I hope I'll be in my studio every day, energized by making art. I dream of solo shows in Europe--the photography museum in Budapest and Freud museums in London and Vienna thrill me. Dreaming and working towards this excites me and creates momentum. My advice to my future self is: Always be grateful--but grumbling can be invigorating. Be kind and gentle to yourself and others, as much as you can. Make art, hang out with your friends.

What projects are you working on right now?

I'm currently working on submitting my work for publication in literary magazines and applying with a friend for an exhibition at a gallery in New Orleans. I use found, black and white photographs from the nineteenth century, called cartes de visite and cabinet cards, to make 4x6" collages. Alterations are done by hand on a small scale, using ink, dust, and glue, then reproduced digitally to create 8x10” portfolio prints and l30x40" archival photographic prints. My works respond to ways in which, throughout the industrial revolution, photography and advertising were employed in the construction of identity. Standards of living improved for some, but income disparity increased. The U.S., an agricultural economy fueled by slave labor, underwent a painful transformation, reinventing itself as a consumer culture in an increasingly industrialized environment. Originally, these photographs encouraged feelings of connection to distant people, places and times. I interrupt these (now unknown) narratives—recycling and creating new meanings, responding to the content, and the physical objects themselves by working the surfaces. I deconstruct and reassemble flotsam and jetsam from the industrial revolution into works whose beauty arises out of a process that nearly destroys the materials, alluding to metamorphoses, dark histories and gothic struggles.

How do you keep yourself accountable in your practice?

I’ve become more focused—taking pleasure in working in my studio most days, and staying true to my passion—making art that reveals the transfixing beauty, ugliness and horror of the world and what it means to be human. I take my own measures of success very seriously and am usually less concerned about others’ ideas of what I’m supposed to be doing. Applying for publication and exhibition opportunities motivates me to keep my business papers in order. I research artists calls to identify galleries and publications that are a good match for my work. I focus on details of what matters, but I do things I don’t enjoy—such as framing—in the simplest manner possible. I’m usually able to give myself credit for successes, take responsibility for mistakes and let go of disappointments. I have coffee with friends and mentors to discuss progress on our work, and schedule studio visits. These meetings cheer and strengthen me, revealing new ways of seeing my work, and help overcome obstacles. I treasure my studio time and make time to give others a hand when I can.

How do you stay motivated to pursue your creative work?

I get so much joy from the process of making art. I love my materials—the beauty of ink, the images and textures of nineteenth century photographs. I try to get in the right mindset to work. On days I don’t feel motivated, I alternate between doing easy things and hard things. I like trying new things, inventing new ways of working surfaces, inventing beautiful/hideous color combinations. I avoid people who aren't supportive of my work. I read, dream, visit archives, do research and look at others' work. I try to eliminate mundane problems in my work so I can focus on the important stuff. That means I make work that’s light enough for me to carry, small enough to store, using materials I can afford. Focusing on my strengths is helpful. Taking on new, possibly scary, challenges excites me. I try to leave jealousy behind. As a kid, although I visited art museums and read about art, I never knew women artists existed. That absence lights a fire in me to claim my voice and communicate my own inner world. I’m tenacious. I’m comforted knowing I’ll never, ever quit, no matter what.

Where do you hope to be 10 years from now and what would you like to say to yourself?

In ten years, I hope I'll be in my studio every day, energized by making art. I dream of solo shows in Europe--the photography museum in Budapest and Freud museums in London and Vienna thrill me. Dreaming and working towards this excites me and creates momentum. My advice to my future self is: Always be grateful--but grumbling can be invigorating. Be kind and gentle to yourself and others, as much as you can. Make art, hang out with your friends.

Julie Blankenship